Designing for volunteers

4.1 Who are the volunteers?

Volunteers are the most important part of any crowdsourcing project. This section will provide guidance around user-centered project design.

4.1.1 Building an ethical project

Research crowdsourcing differs from traditional micro-work platforms (e.g., Amazon’s Mechanical Turk) in that volunteers are not paid for their labor. Because of this, it is your job as a project creator to consider how your volunteers benefit from taking part in your project. Below are some important ethical considerations to bear in mind while crafting your project.

Rebecca Schneider, Associate Director, The Gravestone Project:

“Backward, or User-centered design principles helped us to conceptualize who else might use the data we hoped to generate and how that data could be used in other disciplines, as well as by non-academic stakeholders. It was thrilling to consider design choices with these other users in mind. It also struck me as an essentially ethical concern to plan for both anticipated and unanticipated consumers of the data (to the extent that’s even possible).”

4.1.1.1 Know your values

According to The Collective Wisdom Handbook (Ridge, Blickhan, Ferriter et al.), reflection on the power dynamics present within crowdsourcing projects can help to empower crowdsourcing project creators to “create equitable and transformative spaces, communication, and activities.” We strongly encourage teams to establish their values at the start of their project planning, and to revisit these values throughout the project lifecycle. As the Handbook also states, “Failing to articulate what is important, and how you will demonstrate it, will lead to you missing a vital component of how your project is organized.”

4.1.1.2 People-forward thinking

Keep volunteers in mind at all times. Part of creating a good crowdsourcing project is considering the perspective of the people who will be taking part in your project. How can the design choices you make create a positive user experience? A great way to ensure you’re engaging in people-forward thinking is to try out other projects – creators who take part in other crowdsourcing projects as volunteers tend to have an easier time thinking about the volunteer experience.

4.1.1.3 Don't waste volunteers' time

You must have a plan for working with your data before you launch your project.

The most common problem for transcription projects is teams not being prepared to use their resulting data. Before you involve the public, you must have a plan for how you will aggregate, review, clean, and store the transcriptions produced through your crowdsourcing project. If you do not know how you will do one or more of these things, you risk asking the public to donate their time, only for the data never to be used. Wasting volunteers’ time is the cardinal sin of crowdsourcing, and something to avoid at all costs.

4.1.1.4 Always experiment and iterate (even before Beta testing)

Putting in the additional effort early and often in the process will require more labor for you and your team, but it will almost always result in a better experience for your volunteers—and higher-quality results. You should walk through your Workflows and Tasks at every step of your process (even before building your project in Zooniverse). It is almost always helpful to also have people less familiar with your data go through the Workflow to uncover assumptions you may make based on your own expertise.

Case Study: Working with difficult materials

The Crocker Land Expedition focuses on a 1913 exploration of the existence of a huge island called Crocker Land that famous explorer Robert Peary claimed to have seen. Although we now know the land does not exist, the expedition to the area produced important scientific research. As part of the BCCCT cohort Rebecca Morgan explored how the Zooniverse could be used to create a platform for transcribing the diverse material gathered by the expedition, much of which is held at the American Museum of Natural History.

Rebecca Morgan, Project Director:

“I wonder about building a community of people that are working on documents that might potentially over you know, days or an hour or whatever, affect them. The [subject sets] may seem innocuous, innocuous on the outside, but after immersing yourself in however many profiles of Sing Sing prisoners or a whole tome on interactions with Indigenous folks and animals, they can take a toll. Especially if you're not ready for it, it can take its toll. And I'm not saying necessarily that it's a bad toll and seeing how important the close reading, skill development... These materials demand some perspective, some thoughtfulness, but I think if someone's just jumping into this to pass the time, or for fun, I don't know if we need trigger warnings on stuff, but we need to figure out a way to work with it and what we owe our community as far as being explicit about that.”

4.1.2 Finding your community

One benefit of using Zooniverse for your crowdsourcing project is the built-in community of millions of potential volunteers. However, not all registered Zooniverse volunteers will take part in your project—you should expect to do some recruiting of your own. Ideally, you want a mix of people familiar with the Zooniverse platform as well as those who bring existing expertise or interest in your subject matter. Publicizing your project on subject-specific listservs, community message boards and via social media accounts can help create interest from others with an existing interest in your project topic. Finding a blend of these groups will help to create a well-balanced community who will not only help your project, but can assist one another with technical questions as well as tricky transcriptions. Read more about building communities in Section 6.

4.2 Home page

A major part of designing a successful project is writing effective copy. On the Zooniverse platform alone, there can be dozens of other projects to choose from, let alone the rest of the internet—what makes yours special? Why should people donate their time to helping you?

Take time choosing a project name and writing the project description and Introduction. These are the first things people will see when they visit your project, so make sure they are accessible and interesting. Avoid long exposition and project history, as this information can go in the About page. Use action words, avoid jargon, and make sure to mention your main Task type. For example, in this case, “Help us transcribe XYZ…” is more effective than “We are digitizing XYZ and want to create digital searchable text via crowdsourced transcription.” For more on writing an effective call to action, see The Collective Wisdom Handbook chapter 9, “Supporting participants.”

4.2.1 Making use of images

The images you include in your project (illustrative images that aren’t Subjects to be Classified) should help volunteers better understand what you are asking them to do (e.g. screenshots of the project’s user interface), or illustrate concepts you are trying to explain (e.g. page layout, script types, etc.). Upload images via the Media tab of the Project Builder. You can resize images before uploading, or after uploading using Markdown. We recommend keeping your Media images under 500KB, to avoid long load times. Modifying screenshots of your user interface can quickly help volunteers understand what you are asking them to do.

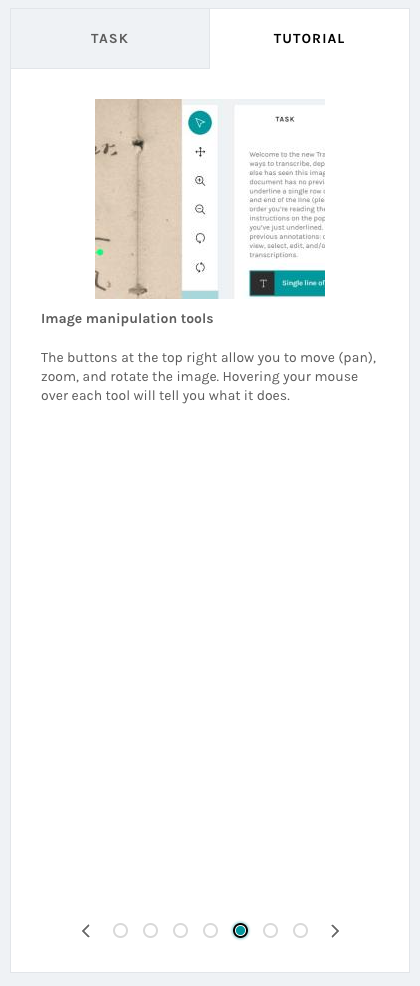

Above: A Tutorial screenshot from People’s Contest Digital Archive, Project Coordinator Kevin Clair.

4.2.1.1 Media

The Media tab of the Project Builder allows you to upload media to your project (such as example images for your Help pages or Tutorial) so you can link to it without an external host. To start uploading, drop an image into the gray box (or click ‘Select files’ to bring up your file browser and select a file). Once the image has been uploaded, it will appear above the ‘Add an image’ box. You can then copy the Markdown text beneath the image into your project, or add another image.

4.2.2 Markdown

The Project Builder supports Markdown, a markup language that allows you to create formatted text via a plain-text editor. The Project Builder features a short Markdown guide, which you can reach by clicking the ‘?’ icon in the upper right corner of any text entry field. A more detailed Markdown guide is available at https://help.zooniverse.org/next-steps/markdown/

4.3 Talk

'Talk' is the name given to the message board system that comes with every Zooniverse project. This section will explain what Talk is, and how to use it to the advantage of your project as well as your community.

4.3.1 What are Talk boards for?

‘Talk’ is the name for the discussion boards attached to your project. On Talk, volunteers can discuss your project and data with each other, as well as with you and your team. Maintaining a vibrant and active Talk is essential for keeping your volunteers engaged with the project. Conversations on Talk can also lead to additional research discoveries, as volunteers bring their own interests and expertise to the project.

4.3.2 How to build Talk boards

In the Talk tab of the Project Builder, first activate the default Subject-discussion board, which hosts a single dedicated conversation for each Subject you upload to the project. Then add additional boards for conversations about a general topic. Examples might include: ‘Announcements,’ ‘Project Discussion,’ ‘Questions for the Research Team,’ or ‘Technical Support.’

To get email notifications when volunteers post on Talk, make sure you 1) have your Notification preferences turned on, and 2) have checked your Talk email preferences. Both can be adjusted at zooniverse.org/settings (this page is also accessible by clicking on your username in the top right corner of the screen).

4.3.3. Talk examples

PLACEHOLDER

Case Study: Keeping up with Talk

The People’s Contest Digital Archive is a project led by the Richards Center at the Pennsylvania State University to transcribe Civil War era documents from Pennsylvania. Transcribing through the Zooniverse platform was an opportunity to broaden access to documents in collections at Penn State and elsewhere in Pennsylvania.

Kevin Clair, Project Coordinator:

“It is important to keep up with the Talk boards in your Zooniverse project every day, especially at the outset (after your launch). There will be a great deal of activity, and most of it will be questions about Zooniverse itself, or about the materials you have made available for your transcription project. The Zooniverse team are very quick with responses to technical questions if you forward them along, but only you will be able to answer questions about your materials (and you will get them!).

You will notice, after your project has been around for a while, that your Talk boards will take on a life of their own and you will not need to monitor them as closely. Most of the responses we have received in the People’s Contest Digital Archive have been to point out blank pages for others, or to note pages that have been damaged or are otherwise unreadable. Also, some volunteers will also be contributing to other digital humanities projects on Zooniverse, and will be able to provide answers to people’s questions or help to fix problems they are having with the platform—in many cases even before you or the Zooniverse team know that they’re a problem…

Our Talk boards have also led to improvements to the project itself. Once enough people have asked the same questions about how to transcribe something, it’s time to add it to our Tutorial or Field Guide so we have a resource to which we can point people.”

4.4 About pages

The About pages are a space for you to share details about your project, its history and outcomes. This section will provide details on what type of information to include, and how About pages can be a source of support for project volunteers.

4.4.1 Research

This section should include the project background (including any funding sources), brief historical context (what will this work contribute to the field?), project goals (including any related work happening outside the Zooniverse project), and planned research outputs (in particular, where volunteers can plan to access project results). Essentially, this is where you have space to justify to volunteers: 1) why you need their help; and 2) how their efforts will affect the research.

4.4.2 Team

Who is working on this project? This section should list all project team members, their institutional affiliation, research specialization, and specific role within the project. Photos are encouraged, if team members are comfortable sharing. Additionally, if there is a specific email address volunteers should use to contact the team, this is a great place to put that information (if you haven't yet, you may want to consider establishing an email address for your project). The Zooniverse username of all Collaborators will be listed here as well.

4.4.3 Results

This section should include links to results when available, and will ideally also include a short description of project results. Before results are available (e.g. at the project launch), we encourage you to signpost where you are planning to host the project results. This communicates to potential volunteers that you understand the platform requirements for making data publicly available and are committed to doing so.

4.4.4 Education

This section is where you can share resources for educators, students, or anyone interested in learning more about your research topic. It is a great place to include additional reading or considerations. You can also post resources that may be used in conjunction with your project, such as syllabi and pedagogical tools.

4.4.5 FAQ

This section should list frequently asked questions about your project. You can start by including anticipated questions, but the expectation is that you will add to this list after your initial beta test, as well as after the project’s public launch.

- Keep FAQ items concise and easy to read.

- Bulleted lists are preferable to paragraphs of text.

4.5 Tutorial, Field Guide, and Help Text

You can support volunteers with additional information in three places. There may be some overlap in the content of these resources, and volunteers will encounter them at different points in their work.

Content for each of these resources is rendered with Markdown, so you can use any media you’ve uploaded for your project in this space. Upload media for your project (illustrative images that aren’t Subjects to be classified) in the Media tab of the Project Builder. Visuals help tremendously in making your support resources easier to understand.

4.5.1 What is a Tutorial?

Tutorials appear the first time a volunteer opens a Workflow on your project. You can use the Tutorial tab to build a step-by-step guide to participating in your project. Tutorials are Workflow-specific; if your project has multiple Workflows, you should design a Tutorial for each one. Volunteers should come away with an understanding of your basic project goals (why are you doing this?) and what they will be asked to do if they choose to participate. You can upload images and enter text for each step. There is no limit to how many steps you can add, but we encourage you to aim for 6 steps or fewer. Remember: the longer your Tutorial, the less likely it is that volunteers will read the whole thing.

Assign Tutorials to your Workflows via the Workflows tab of the Project Builder. More info on writing Tutorials is available on the Zooniverse blog.

IMAGE PLACEHOLDER

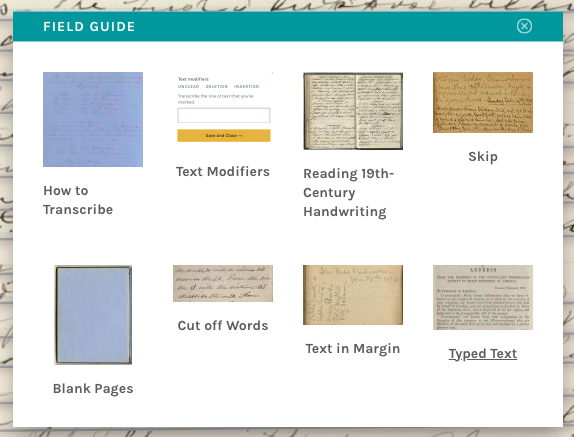

4.5.2 What is a Field Guide?

The Field Guide is a space for you to provide information on the project content that helps volunteers become more proficient at interpreting your source material. Examples might include frequently-used abbreviations, lists of common places and names, or explanations of period-specific writing conventions (e.g. the long s, cross-writing, etc.) Information can be grouped into different sections; each section should have a title and an icon. The Field Guide can also host a general background to your material and research Subject.

Above: A screenshot of a Zooniverse Field Guide topic list from People’s Contest Digital Archive, Project Coordinator Kevin Clair.

Above: A screenshot of a Zooniverse Field Guide topic list from People’s Contest Digital Archive, Project Coordinator Kevin Clair.

4.5.3 What is Help Text?

You need to provide Help text for all Tasks in your project Workflow(s). This information should help volunteers complete the Task they are currently being asked to complete. It is a space for specific instructions on how to use the tools provided for that particular step of the Workflow, not necessarily how to interpret the content (that’s what the Field Guide is for).

Case Study: Talk support

Letters to and from authors provide scholars and readers with new insights into what authors were thinking about that didn’t make it into print. In the Maria Edgeworth Letters project, transcribing letters held in one place makes the material more widely accessible and provides volunteers with exciting opportunities to learn more about the thoughts behind the printed word.

Hilary Havens, Co-Principal Investigator:

“One of the most challenging and time-consuming, but also one of the most rewarding parts of the project has been interacting with volunteers on the Talk Boards. This becomes relevant as soon as your project enters beta testing, but you should work on the Talk Boards even before then. My collaborators and I thought we did a good job with our Tutorial, Help Text, and Field Guide, but once we started seeing comments from the volunteers, we realized how wrong we were! Many of the volunteers – especially the beta testers - were much more experienced than us in dealing with Zooniverse projects and knew exactly what we were missing. Our Help Text for the transcription tool needed to be more specific and have more pictures. We needed to cover many more edge cases in the Field Guide (such as tables, damaged pages, and the British pound sign). The Talk Boards helped us improve our project immeasurably. They also take a tremendous amount of time – especially in the beta period and early weeks of the projects – as the volunteers help the project team explain and improve things.

The Talk Boards also helped us provide guidance to the volunteers beyond the Field Guide, Tutorial, and Help Text. Maria Edgeworth and her circle have difficult handwriting, and we devoted an entire section of the boards to a handwriting guide that an undergraduate research assistant undertook as a project. The guide was very popular with volunteers and editors alike adding numerous entries linked to weird writerly quirks, like Edgeworth’s k’s that look like they have an “e” at the end.

Overall, the Talk Boards have been the place to actually engage with the public regarding the project and share our interest in the material. We have had marvelous discussions with our contributors on topics like Edgeworth’s interest in lace, her views of other writers, her opinions on deafness and disability and how those would be viewed today. Our contributors have found and continue to find allusions to people, places, works, and other things that will be incredibly helpful as we take the project to the next stage: correct the transcriptions, encode the letters, and add notes. We have a dedicated research assistant to help extract information from their posts and find a consistent way to credit contributions from the Talk boards, which is the next step in our plans.”