Getting Started

1.1 Who is this resource for?

This guide is aimed at people who want to transcribe a large amount of handwritten text using volunteer crowdsourcing. You will either have an existing collection of digital images, or have identified manuscript or archival sources that you plan to make digital images of, which will be transcribed through the effort of volunteers. This guide is a comprehensive introduction to the lifecycle of a crowdsourced transcription project using the Zooniverse platform, covering technological and social aspects of such projects.

You may be interested in crowdsourcing because the volume of material you have is larger than you or your research team could transcribe alone. If you plan to ask volunteers to participate, you need to make the transcription process meaningful and rewarding. Thus we carry through this guide an assumption that the material you are interested in transcribing will be of interest to others beyond your immediate use case.

Crowdsourcing text transcription is of interest to a wide range of people. We have tried to write this guide with an awareness of the variety of interests and materials that may have brought you here. Our advice is not tailored to assumptions about your disciplinary background, institutional affiliation, or educational status, though those may well affect how you go about implementing the advice we give. Handwritten pages are important sources for meteorologists and medievalists, physicists and poets, economists and ecologists. Text transcription projects often originate from teams in museums, libraries, universities, government agencies, archives, genealogical organizations, and scholarly societies, but can be hosted by individuals or other organizations, too. A project to crowdsource the transcription of text may take a year or more to complete, and so we assume that you—individually or collectively—can sustain your project over a long period of time, and be comfortable with uncertainty about how long it takes.

This guide was developed as part of an NEH-funded Institute for Advanced Topics in Digital Humanities, Building Capable Communities for Crowdsourced Transcription, that ran from 2021 to 2023. The authors of the guide worked with 15 project teams in seven online meetings and one in-person meeting to build crowdsourced transcription projects on the Zooniverse platform. This guide was informed by the questions and experiences of those projects, as well as our experience designing and teaching the institute.

This guide was written collectively by the Co-Directors of the institute, and its two research assistants.

We have written this guide in the first person, addressing our advice to “you” as a member of a team building a crowdsourced transcription project. When we refer to technical terms related to the Zooniverse we have capitalized the words.

Co-Directors

Samantha Blickhan, Zooniverse Co-Director & Humanities Lead, Adler Planetarium

Evan Roberts, Assistant Professor, History of Medicine and Population Studies, University of Minnesota

Benjamin Wiggins, Senior Lecturer of History and Library & Archive Studies, University of Manchester

Research Assistants

Treasure Tinsley, PhD Candidate, History, University of Minnesota

Trevor Winger, PhD Candidate, Computer Science, University of Minnesota

1.2 How to use this resource

We have written this guide to take you through the entire lifecycle of a crowdsourcing project. We encourage you to read the entire guide as you consider whether crowdsourcing is the right approach for your project and sources, and whether Zooniverse is the appropriate platform for your needs. As you develop, launch, sustain, and wind down your project in the months and years to come, we hope you will come back to relevant sections to consult in more detail.

We encourage you to begin by using this guide to assist you in creating a strategic plan for your project. While there are important common elements to all crowdsourced transcription projects, every project is unique in some way. You must make decisions about what will work best for your source material, goals, and team of people. This guide aims to help you narrow down those choices and understand the tradeoffs.

As you read this guide you will notice that we offer advice about different choices you can make in various phases of your project. Take the time to write down your thoughts about what you will do, and review these before you start the serious work of collecting and organizing images and developing Tasks and Workflows. You should think about when you need the data and how likely delays will affect your other work. Your volunteer community is not working on your timetable. Revisit your strategic plan as you make and implement decisions.

1.3 What is Zooniverse?

Zooniverse is an online platform for people-powered research. Though the platform’s origins are based in astronomy research, the founders of Zooniverse recognized that many research challenges in the modern social sciences and humanities are similar: there is abundant digital media containing information that people want to transform into a format that allows easier manipulation. There is a fundamental similarity between an astronomer asking, “What shape is this galaxy?” and a medieval historian asking, “What words are written on this page?”

Because digital images can be shared easily on the internet, it is possible to ask people all over the world to help us answer questions about those images. The Zooniverse Project Builder is a browser-based tool that allows anyone to build what are essentially sequences of questions posed to people about the image at which they are looking. We will describe the technical aspects of using the Project Builder and how they apply to transcription in this Guide. You should also consult the general Zooniverse guide to building projects at help.zooniverse.org, which will contain the most up-to-date technical information about the Project Builder.

Projects on Zooniverse ask volunteers for help in systematically examining images (or more generally, media) and recording answers about them because the questions being asked about the image are not yet possible for a computer to answer with acceptable accuracy. The boundaries between “what can a computer do quickly and accurately?” and “what can people do more accurately?” are shifting rapidly. Before asking volunteers for help with transcribing, consider whether some of your material could be transcribed by a computer. Computers are becoming better at accurately recognizing handwritten text—some handwritten documents can already be read accurately enough by computers—but for other documents the human eye still rules. Data from Zooniverse and other transcription projects is already being used to improve how computers read handwriting. As you develop your project, we encourage you to be aware of these possibilities and collaborate where you can with people trying to improve these methods. For more information, see “Preface” (Wanamaker, Frydman, and Dahl), which discusses and links to recent work in computer recognition of handwriting.

Zooniverse is also a community of project creators and volunteers who connect online about the projects on which they are collaborating. Developing a community of volunteers who will spend time on the project that you create is a distinct challenge from designing and building the project itself. Finding and encouraging people to spend their time on your project, and to keep them engaged and motivated, is a social challenge. We encourage you to think about who might be interested in the material you want to transcribe. When a project launches publicly, Zooniverse will publicize it to an email subscription list of several million people. Every project launch is a chance to engage existing Zooniverse volunteers as well as new volunteers who join the platform because they are interested in that new project.

Transcription projects often draw on audiences interested in history, genealogy, literature, the culture of the place the writing comes from, and the history of particular institutions, organizations and topics.

Above: Mary Leadbeater to Benjamin Haughton, July 16, 1804. University of California Santa Barbara Mss4, Box 6, folder 8, 001. From Corresponding with Quakers, Principal Investigator and Project Director Rachael Scarborough King.

1.3.1 Project Builder broad overview

The elements of a Zooniverse project are simple. You have a collection of images which contain information that is best extracted by asking people to look at the image and do something. The Project Builder allows you to upload the images, ask people a set of questions about the image, and export the answers that people provide. Zooniverse projects feature multiple, (typically) independent classification, meaning more than one person will respond to the questions being asked about each image. By comparing the answers that different people give to the same question about the same image, you can be more confident you are getting an accurate answer. In general, crowdsourcing has been proven to be a reliable method for generating high-quality data, even at expert levels, and a number of Zooniverse projects have resulted in publications demonstrating the reliability and usefulness of crowd-generated data.

The Zooniverse platform stores the answers that different people give, and makes it available to you for download as a CSV file. You will use your knowledge of the material to decide how to combine the answers that different people give into a single answer that best represents the material you are transcribing: this is called Aggregation.

Because text transcription is a popular and complex task, Zooniverse has developed additional tools for aggregating text data and reviewing transcription project results. For more detail on data aggregation, see Section 7.

1.3.2 Outlining the Zooniverse project process

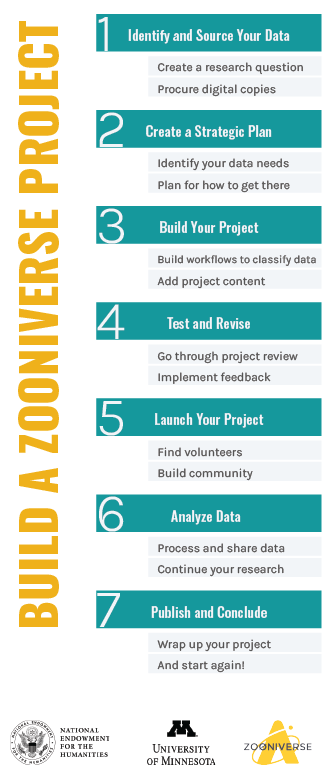

This graphic represents seven high-level steps required to build and launch a public Zooniverse project (i.e. one that is listed on our Projects page).

1.3.3 Project input: overview

To build a project in the Project Builder you will need a collection of digital images of the material you want transcribed. You do not need all of your images right away. You should know the provenance and usage rights for each image, and have a plan in place for organizing information about the data you are using, such as a spreadsheet. If you are using images of material in a library or archive, the file reference of the images is information you should plan to save along with the image names.

1.3.3.1 What is a Subject Set?

Transcription projects often involve collections of related pages that you likely want transcribed together. For example, it is not very helpful to have one random page of a set of multi-page letters transcribed. You probably want related pages transcribed together. Subject Sets allow you to group related images to be transcribed at the same time, so you can examine the output (text) from those images together. See Section 2 for more detail.

1.3.4 Project output: overview

Zooniverse projects allow you to collect multiple transcriptions of the same text. We find that 2-5 people transcribing an image is sufficient to produce a generally accurate transcription without wasted effort. Not every volunteer will write the same thing, so you will need to aggregate the data into a harmonized or consensus version that best represents the original material. Zooniverse provides a tool for aggregating lines of text transcription which can be used for certain transcription project types, and also provides Python scripts to assist with aggregation of data produced by other tools available in the Project Builder. As a project creator your knowledge of the material and plans for using the output should shape how you collect and aggregate data. For example, if you are producing an authoritative edition of a manuscript you will be less tolerant of spelling mistakes than if you are coding or classifying text into numeric categories for quantitative analysis.

The interests of project creators will shape the way that data is initially collected and aggregated. Zooniverse requires that you make your data publicly available within two years of your project’s completion. Therefore, you should ideally collect and aggregate data in a way that will be useful to other people interested in the material you are transcribing. Try to anticipate how others might want to use your data when putting together your strategic plan.

The aggregated consensus output (i.e. the ‘approved’ transcription data) is likely to be most useful to other people interested in your material. However, when you conclude your project you should also make available the larger, unedited dataset of transcriptions and the code used to transform these into aggregate output.

1.4 What is crowdsourced text transcription?

This section will provide context around methods and history of crowdsourcing, with a focus on transcribing text. It will dive into ethical approaches, motivations for transcribing, and best practices for developing goals and objectives for your project.

1.4.1 What is crowdsourcing?

Historically, crowdsourcing was conceived of as a way to outsource labor to the crowd via an open call (Howe). This model of crowdsourcing persists today as microwork (see for example Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, Appen or Clickworker, all of which pay gig workers on a per-task basis to produce training data for machine learning models). Since the term was first used in 2006, research crowdsourcing has largely deviated from the original definition in the sense that it is not paid work, but a way to involve the public in research in meaningful ways.

For a text transcription specific definition of crowdsourcing, we look to The Collective Wisdom Handbook: perspectives on crowdsourcing in cultural heritage: “At its best, [crowdsourcing] is a form of digitally-enabled participation that creates meaningful opportunities for the public to experience collections while undertaking a range of tasks that make those collections more easily discoverable and usable by others.” (Ridge, Blickhan, Ferriter, et al.)

The most common humanities crowdsourcing task is text transcription, in which volunteers help to create digital, searchable versions of text found in digital images of archival records.

1.4.1.1 The ethics of crowdsourcing

Because there is no financial reward for taking part in crowdsourcing, it is up to practitioners and project creators to produce “human-centered projects that deliver benefits to all involved” (Ridge, Blickhan, Ferriter et al.). The best way to ensure you are creating an ethical project is by establishing values and letting those values drive your project design and testing processes as well as the ways you involve and engage with volunteers.

Values are broad, and can include everything from committing to only publish project research in open-access journals, to including warnings on projects dealing with potentially traumatizing content, to clearly articulating how you plan to acknowledge volunteer effort in publications. Values can and should evolve over the course of your project. A good project includes places where you and your team are able to take a moment to check in on your values and either update them based on your experiences, or actively choose to keep them. Your project cannot be values-agnostic; choosing not to articulate your values is de facto support of existing power structures (Ridge, Blickhan, Ferriter et al.).

Human-centered projects mean keeping people in mind at every stage. When designing your crowdsourcing project, consider this: how do volunteers benefit from helping transcribe this text? What can you do to ensure a positive user experience, and make sure that volunteers’ labor is being used efficiently? If you are working with students, how are you accounting for the additional power dynamics in place within the student/teacher relationship? Zooniverse requires all project creators to make their data publicly available within two years of the project’s completion—how does your data management plan account for this requirement? These framing questions can help you get started thinking through the ethical considerations of your project; further ethical issues are considered in Section 6: Acknowledging Volunteers.

1.4.2 Why transcribe?

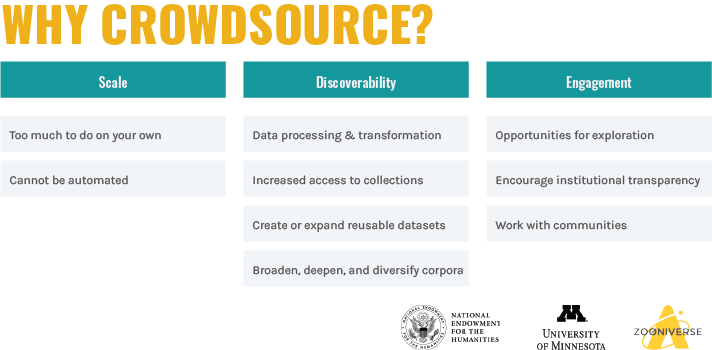

Before getting into the specifics about why you want to transcribe, this table will help you think more broadly about why to crowdsource more broadly.

1.4.2.1 Identifying your needs

If your motivations are only coming from one of the above three categories (Scale, Discoverability, or Engagement), there’s a good chance you’re going to run into problems. Either you are too focused on data and not focused enough on people, or you’ve put too much of a focus on the public project itself and haven’t given enough thought to your data management practices or whether you even need to ask the public for their help.

1.4.2.2 Is Zooniverse the appropriate platform for your project?

Zooniverse projects benefit from 1) the ease of using the Project Builder; and 2) the size of the existing volunteer community. With that said, designing, building and running a crowdsourcing project requires a lot of effort and resources, especially in the form of staff time. Planning out your project in advance will help you confirm that you have the resources and bandwidth to take on this responsibility. For more information on selecting platforms, see The Collective Wisdom Handbook, Ch. 7, Aligning tasks, platforms, and goals.

Case Study: New tools for transcription at scale

The People’s Contest Digital Archive is a project led by the Richards Center at the Pennsylvania State University to transcribe Civil War era documents from Pennsylvania. Transcribing through the Zooniverse platform was an opportunity to broaden access to documents in collections at Penn State and elsewhere in Pennsylvania.

Kevin Clair, Project Coordinator:

“As a librarian tasked with digital collection stewardship, my team and I are always interested in new ways to provide access to our collections for users and to engage with our community in new and interesting ways. For us, publishing our collections as data opens them up to new methods of analysis and can allow connections to be made between materials in the collections that can’t be made through resource description or close reading alone. Working with Zooniverse, particularly with a project that already had a degree of existing transcription, gave us the tools and the impetus to find a methodology for publishing transcriptions at scale that we could refine for future projects like this.”

1.4.3 Develop research goals and objectives

Goals are high-level ideas, and objectives are the actions you take in service of those goals. You should identify your project goals and objectives early on in the project planning process.

1.4.3.1 What are your broad research goals?

Your goal here is likely to create digital, searchable text through crowdsourced transcription. Do you have additional research goals that are related to the content of the transcribed text? It helps to map out the full extent of your project goals at the start, as this should drive your decision-making process.

1.4.3.2 Breaking your project into smaller pieces (objectives)

For the goal of creating digital, searchable text through crowdsourced transcription, objectives might include identifying team members, creating a data management plan, identifying and securing funding, designing Workflows, and getting buy-in from institutional administrators.

Kevin Clair, Project Coordinator, The People's Contest Digital Archive:

“Methods for measuring engagement are also something that digital collections programs have found elusive. Having engagement visible as directly as it is with a community transcription project – through the Zooniverse Talk boards, or even through the steady stream of subjects awaiting final approval – is something we can take directly to supervisors and administrators to document the impact that our digitization program is having on visibility of digital content from the library.”

1.4.3.3 What should be done through Zooniverse?

As the list above shows, not all of your goals and objectives will take place on Zooniverse, though there will be many points where the success of your ‘offline’ objectives directly impacts your Zooniverse project. When mapping out your goals and objectives, take care to consider what tasks truly need to be crowdsourced, and what can be done internally—often, the labor required to work with crowdsourced data can outweigh what would be required for institutional staff to do the work themselves. You should also explore what parts of your project could be performed by a computer—what is technologically feasible is changing rapidly and will vary across different sources. Thinking through the full scope of your project can help you to identify what scale of project you are able to take on.

Case Study: Developing a strategic plan

Deciphering Secrets: Unlocking the Manuscripts of Medieval Spain brings medieval Spanish manuscripts online, and provides volunteers with the opportunity to learn paleography before participating in transcription.

Roger Martinez, Project Director:

“I think the challenge here is that, as humanists start to work more closely with technology, we weren't trained to use these types of materials and then we don't know the critical kind of steps you have to run through. It's not like in history, where we know that you’re going to do something like a historiographical session, we're going to present an argument... you don't have the same kind of guideposts.

You don’t know what you don’t know. So I think the steps have to be related to, starting with the highest level, what are the goals and objectives of the project? And from there, it’s really, how are you going to measure and assess your progress towards those goals? Then also, for the next step, really thinking through, ‘Okay, so what are some of the specific strategies I might implement that will move in this direction?’ And then, what do the deliverables look like at the end. You have to think about this as a strategic planning process.

This is part of the conversation that's happening out there right now is there’s this expectation that by using this crowdsourcing technology or processes that it will make it easier for you to do things and I think what we realize is though, it doesn't actually make things easier, it just facilitates a type of greater engagement of many people working on a common project. So collective action.”

1.5 Early considerations

This section will signpost some things to think about early on as you begin to conceptualize and design your project.

1.5.1 What are your short- and long-term goals?

A clear understanding of your broader project goals is vital as you develop your plan for crowdsourcing the transcription of handwritten text. We noted earlier that we make few assumptions about your disciplines or background. But whatever discipline you are working in, Zooniverse requires that projects have the goal of producing useful research. Across the diversity of your research fields it is likely that your goals are to:

- Produce data (text) that you share so that other people can study the text, and present and publish results.

- Produce data that you will initially analyze, present, and publish. You will then make the data public in accordance with Zooniverse policies.

Crowdsourcing takes time. Sometimes it proceeds more quickly than expected, and other times more slowly. You should identify short-term analysis, presentation, and publication objectives that can be achieved with only a small share of the text transcribed and aggregated. What is a particularly interesting subset of your data that you can write about? In transcription projects these subsets of the data are often identified by the project leads. Some science projects might be able to use a random sample of images, but this probably doesn’t work for letters, diaries, and drafts of literary works. Identify your highest priority material, and prioritize those images for transcription. Using early results to demonstrate that volunteer work is contributing to discoveries and being shared is tremendously encouraging for your volunteers, and can help with volunteer retention, especially in long-running projects.

Showing initial results and the viability of your work is also important in seeking more funding for your project. Grant funds can help provide your team with the additional skills and resources it requires (see Section 8).

Working with volunteers can take your work in new and unexpected directions, as you collaboratively discover unexpected things via the initial transcriptions. Only you can decide whether to pursue these new directions by evaluating them in relation to your long-term goals.

Articulating long-term goals is important for all transcription projects. For projects led by one or two people, clearly stating long-term goals will help you prioritize your work as your project progresses. Crowdsourcing projects led by a small team can falter when there are other demands on people’s time. Articulating long-term goals at the beginning of a project can help larger collectives and institutions with structured discussion of where a project is going, and help with aligning staff work with project needs.

We encourage you to build towards your long-term goals with a series of short-term achievable objectives that can be communicated to volunteers and other collaborators.

1.5.2 Where will your project and its data live?

Zooniverse provides all projects with an online transcription interface (where the work of volunteers is done) and a dedicated message board, called Talk, where you can interact with your project community (see Section 4.3). You should also consider how to develop a presence for your project in other ways, both online and offline (see Section 6 on working with volunteers).

Many projects have established separate websites that give further background on the broader goals of the project. These are most often hosted by affiliate institutions. Project-specific social media accounts can also be useful in calling attention to your work, recruiting volunteers, and publicizing data and publications. Because the social media landscape is rapidly changing and project needs vary, we do not give advice on which platforms to use. We do recommend that you establish an identity for your project that is separate from the personal or professional accounts of project leaders (though they can and should amplify project messages).

When you have data to share, a project website can be an additional venue for publicizing the availability of data by linking to a trusted data repository. It is vitally important that you have robust systems for storing your images, programs and data. Because the work of crowdsourcing projects is collaborative, you should develop a system that allows data and programs to be shared and accessed by all members of your team, and a workable system for communicating about your project.

When you have developed final aggregated versions of your transcription data, you must share this publicly (see Section 8).

1.5.3 What types of support do you have? What types of support should you seek?

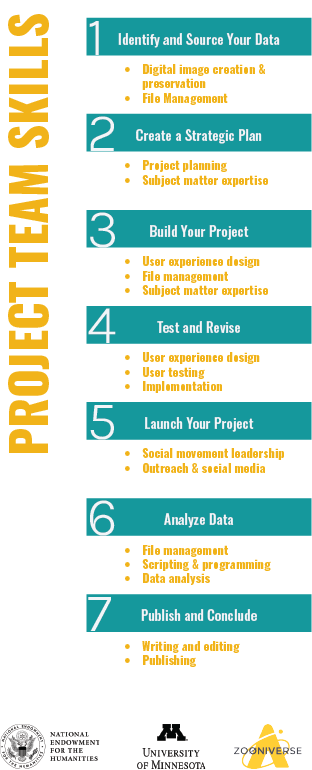

This chart lists the seven main steps of building a Zooniverse project (the same steps shown in the chart in section 1.3.2). Under each is a bulleted list of skills that are helpful at that step.

Crowdsourcing text transcription requires the application of a range of different skills, potentially including digital image creation (photography and digital preservation), organizing and manipulating large volumes of digital images (file management), designing an appropriate Workflow for transcription (user experience design), recruiting and working with volunteers (social movement leadership), data cleaning and analysis (file management, scripting and programming), and presenting and publishing analyses.

This is a wide range of different skills, and it is a rare person who will be skilled in all of the above listed areas. We encourage you to build collaborations with people who have complementary skills, particularly if you are reading this as a lone researcher, or a smaller group of two to three people. If your team does not have the skills required, do you have the time and resources to allocate for a team member to learn them, or can you form a collaboration to bring these skills to your project?

Many crowdsourcing project creators (and potential project creators) are at universities or based in libraries, archives, and museums. Resources for learning these skills are likely available to you via your institution. You are also likely to have colleagues with complementary skills. Collaboration with students or interns who have skills relevant for your project can be mutually beneficial when approached in the right way. If you work with students or interns, ensure they receive appropriate credit and reward for their work. Recruiting collaborators is valuable practice for recruiting volunteers, as you must articulate why your project is interesting, and why other people should become involved.

Identifying the skills and resources you have, what you need, and the gap between them is an important part of your strategic plan for your project. As you read this guide, try to identify areas where there is a gap between your current team’s skills and resources and what you need to construct useful and usable text data. How will you acquire those skills and resources by the time you need them?

Case Study: The benefits of collaboration

Letters to and from authors provide scholars and readers with new insights into what authors were thinking about that didn’t make it into print. In the Maria Edgeworth Letters project, transcribing letters held in one place makes the material more widely accessible and provides volunteers with exciting opportunities to learn more about the thoughts behind the printed word.

Hilary Havens, Co-Principal Investigator:

“I'm very fortunate to be part of a project that has a lot of collaborators. We have four librarians who frequently give us advice. And having them help produce things like the personography, or check our metadata, check our TEI template, make sure we're linking to name authorities . . . having this knowledge that would be very hard for an English professor to acquire is great. And having someone who knows so much about metadata and name authorities takes a lot of pressure off other people doing other things.”